By Nicholas Freudenberg, Distinguished Professor of Public Health, CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy; Founding Director and Senior Faculty Fellow, CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute

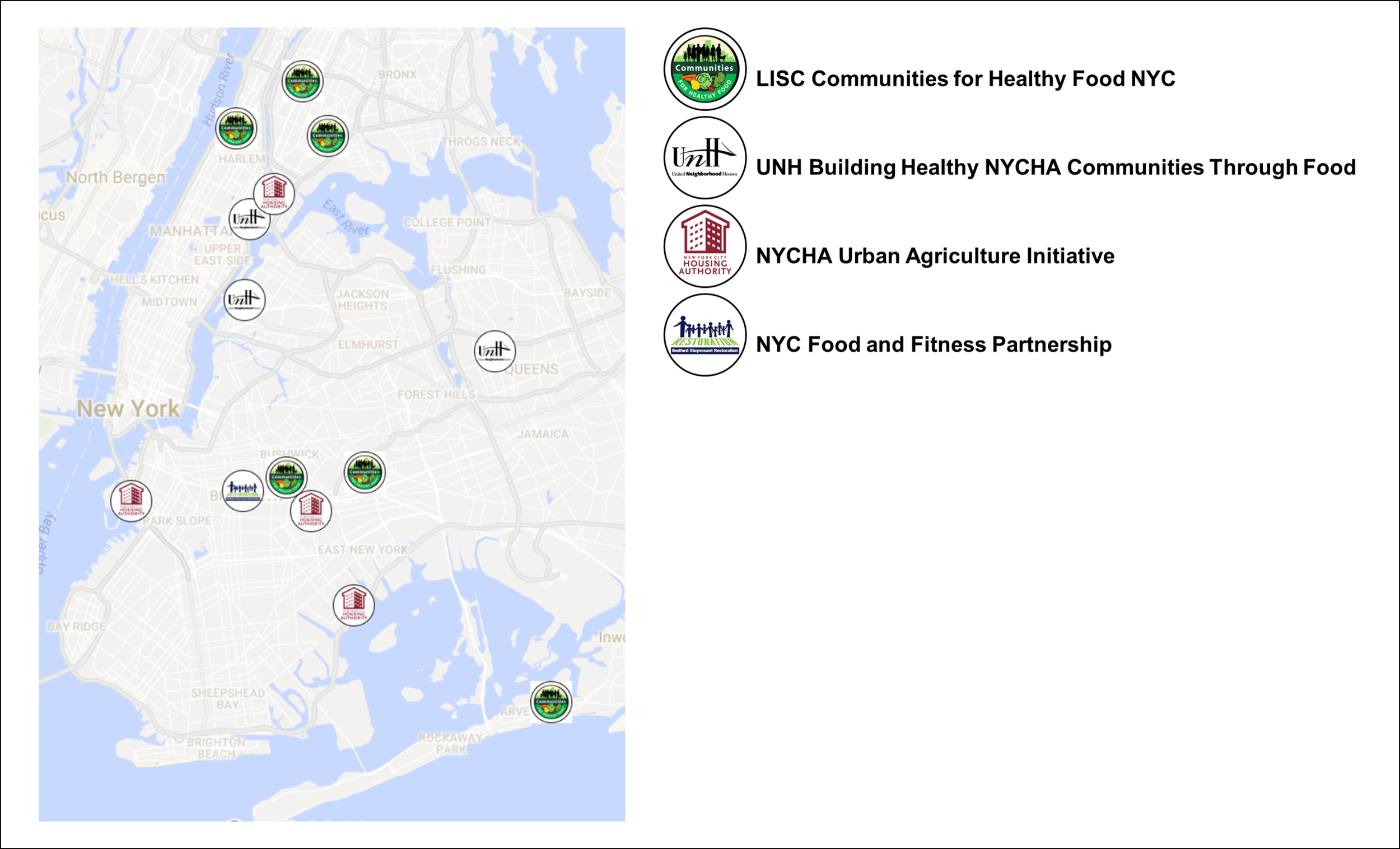

For the last five years, our Institute has been evaluating community food programs in 14 New York City neighborhoods. The map below shows the neighborhoods where we are working and the larger initiatives in which these sites are participating. From my own participation and observation in these evaluation studies, I have come to appreciate both the positive and negative roles that evaluation can play in community food programs and also some of the dilemmas these efforts face. In this commentary, I describe some of the lessons from these experiences and raise some questions about evaluation for the food policy and food justice communities to consider.

Map of Community Food Programs Being Evaluated by the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute.

Evaluation at its Best and Worst

Evaluation has been defined most succinctly as comparing objects of interest against some standard. In the case of community food programs, evaluation studies compare the process, short-term impact and long-term outcome of a particular mix of activities (e.g., nutrition education, retail innovation, urban farms, enrollment in food benefits such as SNAP and WIC) against some intended goals. The comparison can be between what planners say they propose and what actually happens, among outcomes at various sites where the activities are implemented, or between a study population and some comparison population not exposed to the intervention.

At its best, evaluation engages and empowers community residents, helping them to get better services and healthier food environments. It helps frontline staff to do more of the things that are working and fewer that have limited or no impact. It helps managers strengthen programs, make mid-course corrections and deploy limited resources more wisely. It helps community organizations demonstrate that the programs that philanthropy or government has supported are actually making a difference. It shows elected officials that the policies they have implemented are reducing the problem of concern—or identifies other obstacles that need to be addressed to bring about change. If evaluation produces so many benefits for so many, why isn’t it more beloved?

At its worst, evaluation robs resources that could be better spent on serving people in order to collect data that are never used. It takes frontline staff and managers away from their programs without providing compensatory benefits. Evaluators work on a timeline that brings useful evidence to organization long after it is needed. The evaluation studies answer narrow superficial questions but leave the larger question as to whether the program led to changes in food environments, diets or health unaddressed. With all these limitations, is it surprising that rigorous evaluation of community food interventions is often a low priority?

In practice, most evaluation studies combine some elements of these best and worst characteristics. In my experience, the more clearly organizations that sponsor, fund and carry out community food programs define the specific purposes of any evaluation, the more likely the evaluation will produce evidence that can guide practice and policy rather than disappoint. Resolving some of the dilemmas of defining the scope and purpose of an evaluation before it begins may help the parties involved articulate –and achieve– their specific evaluation objectives.

Some Evaluation Dilemmas

Process versus outcome? The first dilemma is between process and outcome. The organizations we are evaluating want to engage community residents in civic action and advocacy in order to strengthen the capacity of individuals and organizations to shape local food environments. Describing the processes they use to achieve these aims allows those working on the intervention to modify what they do as the project unfolds and others to learn from their experience. Sponsoring organizations also want to change outcomes: less food insecurity, lower rates of diet-related diseases, food environments that make healthy food more available and affordable, and changes in the shopping, cooking and eating behavior of the people they serve. Assessing these changes is a prerequisite for distinguishing effective from ineffective interventions and for determining which programs to sustain and expand and which to end.

Stirring Up Community Change Orientation, a project of New Settlement Apartments’ Community Food Action, one site of the LISC NYC Communities for Healthy Food NYC Initiative. Photo courtesy of New Settlement Apartments.

Not surprisingly, many groups often find it a challenge to find the right balance between carrying out and evaluating activities intended to improve community processes and those seeking to change health or environmental outcomes. Two possible solutions:

- Consider dividing implementation into two stages. In the first, the evaluation question is “Can we engage community residents in food activities?” The sponsor focuses on engaging the residents in activities that will contribute to changing food environments. Once they have shown that those processes can be changed, the intervention and evaluation planners ask the second question: “Can these activities lead to measurable changes in food environments or dietary practices?” For example, a program that seeks to improve food environments within public housing by engaging community residents in food-related activities could begin by carrying out and documenting activities designed to bring young children, teens and seniors into food activities by offering cooking classes, community meals, farm visits and supermarket tours. Once the group identified what worked and didn’t work to engage residents, it could turn to a focus on using this engagement to bring about and document changes in food behavior, cooking and healthy food availability. This two-step process can save time (and money) and ensure useful learning from both successes and failures.

- Another approach that some groups have found useful is to collectively articulate the theory of change that connects process and outcome and to develop logic models that can guide implementation of these change strategies throughout implementation. [1] Recently City Harvest brought together its own staff and outsiders to articulate a theory of change that could guide the development and evaluation of the second round of its Healthy Neighborhoods initiative. By considering its experiences in the first round of this multi-site initiative from a variety of perspectives, City Harvest distilled the knowledge of key stakeholders into a framework that could help guide future implementation and evaluation.

Individual vs. Community vs. Municipal Change? Another dilemma is between what weight to give to implementing and evaluating activities designed to change individuals and those seeking community or municipal-level change. We live in a society deeply committed to individualism and most people focus on the end stage of the food process, what the eater puts in her mouth, chews and swallows. Most of us pay less attention to the deeper structural and societal factors that constrain all the choices that lead to that swallow. In my experience, most organizations doing food work devote most of their resources to intervention and evaluation at that individual level. We are convinced that a little more education, a little more motivation is all that is needed to reduce weight, control blood sugar, reduce food insecurity or improve health. From an implementation perspective, it seems so much easier to change what’s inside a person’s head than to change the world in which that head lives. For evaluators, measuring changes in knowledge, attitudes and behavior, the classic outcomes of traditional health and nutrition education, seems more straightforward than measuring changes in food environments or population health. And to satisfy the demands of funders for measurable results, program implementers and evaluators sometimes focus more on what is easy to measure than on important barriers to change.

In public health, however, we have increasingly come to the conclusion that while education and behavior change may be necessary parts of change, they are seldom sufficient. Instead, our goal has become to create environments that make healthy choices easy choices. People still differ on whether you best do that by nudging people to do the right thing or by limiting the powerful interests that promote ill health in order to profit. The community-building approach to food work has the added benefit of focusing our attention on the more upstream determinants of diets—factors such as income inequality, poverty, racism and corporate promotion of unhealthy food. Considering these factors can expand the narrow focus on individual choice that constrains the impact of our work.

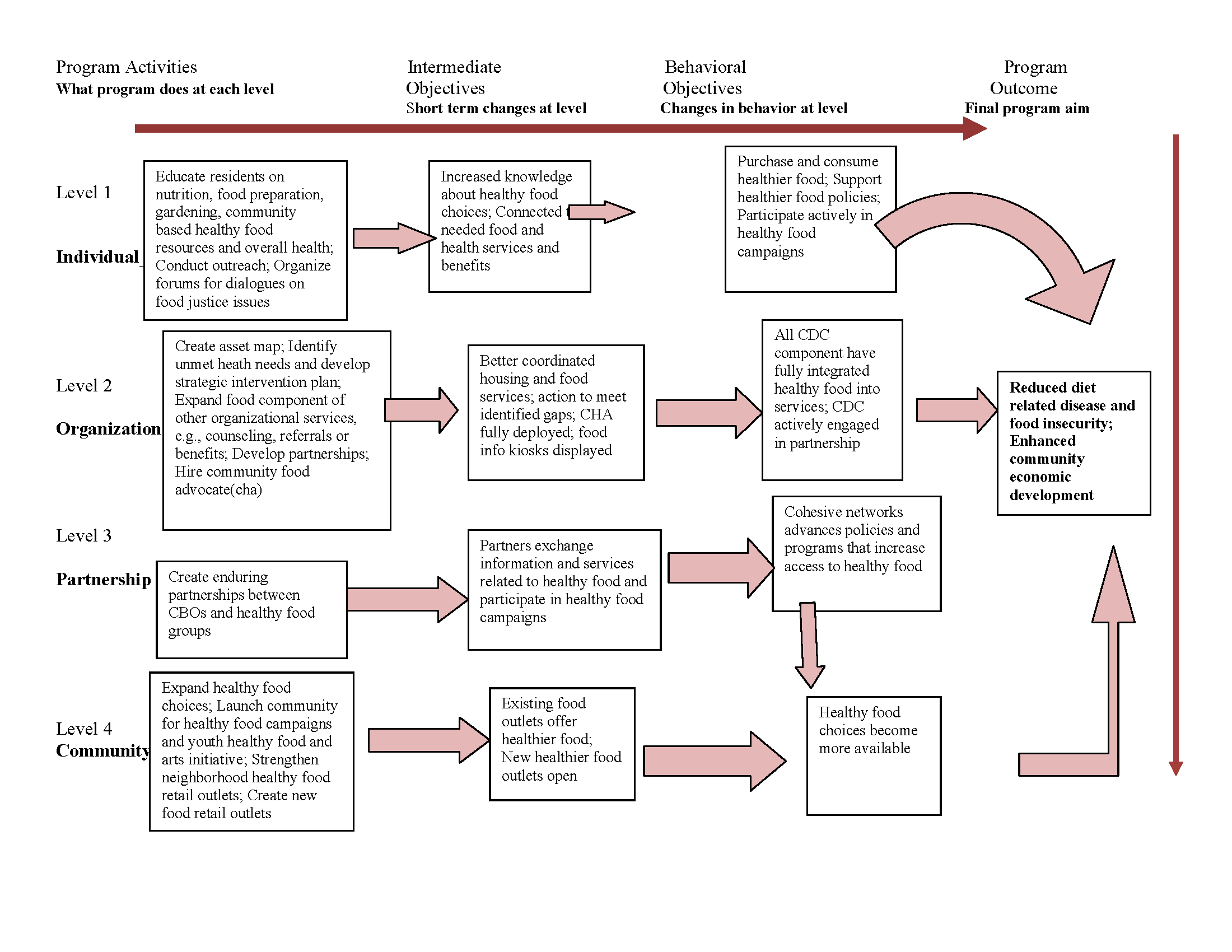

How can program planners and evaluators incorporate these insights into tackling the deeper determinants of health? One useful tool may be the development of multilevel models that can acknowledge and guide work that cuts across levels of organization. The figure below shows a logic model that we have used in our evaluation of LISC’s Communities for Healthy Food initiative. It shows activities at four levels (individual, organization, partnership and community), suggesting that program staff focus on carrying out activities designed to bring about changes at each level and evaluators look to measure the extent of change at each level.

Logic Model: Communities for Healthy Food Initiative

Another approach is called “portfolio evaluation.”[2],[3] This approach recognizes that no single intervention or evaluation has the capacity to solve “wicked problems” like food insecurity or diet-related diseases. Instead, what is needed is a portfolio of interventions, operating at different levels and attacking different determinants of the problems. Especially for larger food organizations, portfolio evaluation provides a methodology for looking at their full range of “investments”, ensuring that programs operating at various levels of organization are adequately balanced to address the multiple determinants of the problems they seek to solve.

Services vs. organizing and advocacy. How can community food programs find the right balance between providing services, whether nutrition education, cooking classes or enrollment in SNAP, and community organizing and policy advocacy? How can evaluators properly balance their assessments of the impact and outcome across these activities? To resolve this third dilemma, we have much to learn from prior experiences in AIDS, domestic violence and food insecurity. In these fields, providing services became platforms for advocacy, a way to bring the voices of people living with a problem into the political arena to educate policy makers, and advocate change.[4],[5] Over time, service organizations organized coalitions to take up the advocacy work and new organizations emerged with an explicit focus on political change. Some of this process has started in food work but I think we would benefit from a more self-conscious and collective effort to address this tension, rather than leaving each organizations to struggle on its own. On the evaluation side, new methods are being developed to measure the impact of advocacy on public opinion, policy and community health.[6],[7],[8] While some funders are understandably reluctant to enter this space, in the coming years, advocacy is likely to play as important a role in changing food environments as more traditional education and services. Shouldn’t we be insistent that these activities are evaluated so we can learn what works and what doesn’t?

Moving From Worst to Best

In New York City, over the last 15 years or so, community food work has proliferated. Hundreds of community organizations and thousands of individuals have strengthened or initiated programs to improve food environments, reduce food insecurity and diet-related diseases and promote more equitable access to healthy affordable food. City, state and federal agencies have launched dozens of new food-related programs and policies. And in this interval, some key outcomes have changed: fresh fruits and vegetables are more available, including in poor neighborhoods, sugary beverage consumption has fallen, and rates of childhood obesity in our youngest children have declined somewhat.

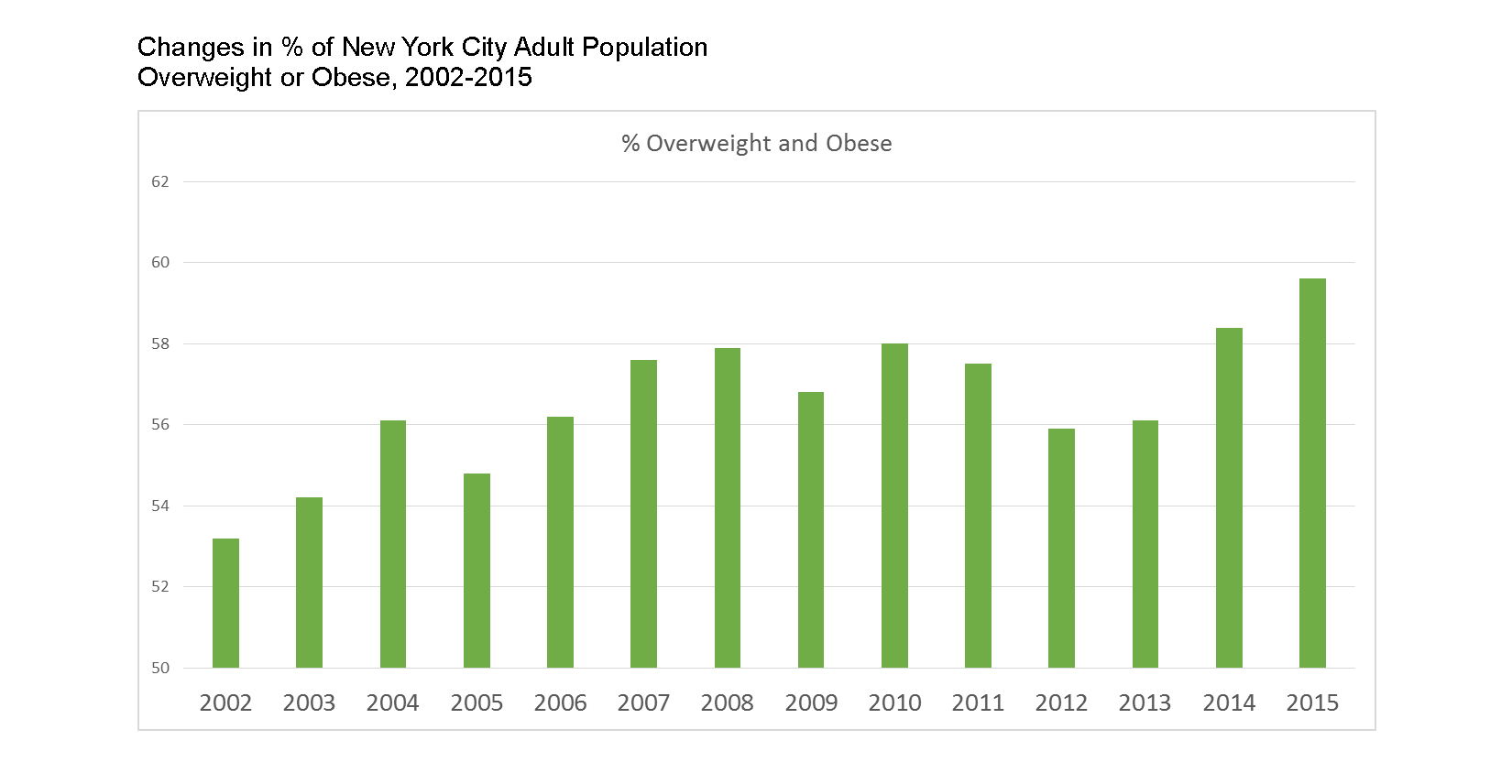

But too many other indicators have not fallen. For example, the chart below shows the rates of overweight and obesity among New York City adults from 2002 to 2015. In 2002, according to the New York City Community Health Survey, 53.2% of adult New Yorkers were overweight or obese; in 2015 the rate was 59.6%. No single metric better captures the future burden of premature death, preventable illness and racial/ethnic and socioeconomic inequities in health from diet-related disease that lies in New York City’s future. Why is it that all our food efforts of the last 15 years have failed to bring this key outcome down?

Changes in % of New York City Adult Population Overweight or Obese, 2002-2015.

Of course there are many plausible answers. Maybe the rate would be even higher had we not launched these programs and policies. Certainly body weight is a challenging indicator to change, especially for adults, whose weight reflects years of conditioning and exposure. And all our laudable efforts to improve food environments in New York City have barely addressed much less reduced what we know are key determinants of body weight: income inequality[9],[10],[11] (which has grown in New York City and the nation over the last 15 years),[12] life-time exposure to poverty,[13] experiences of racism, [14] the deterioration in diet quality associated with immigrant acculturation in high income nations,[15] and exposure to unhealthy food advertising.[16]

Despite these important caveats, at least part of our failure to demonstrate more meaningful changes in diet and health in New York City in the last 15 years is due to our failure to learn from our successes and failures. The limited focus and resources dedicated to evaluation reflects in part our limited effort to coordinate and rationalize the myriad food efforts going on in neighborhoods around the city. The paucity of a body of literature that can guide practice is one of many consequences of an anarchic approach to food policy: every government agency, every nonprofit organization, every academic institution does their own thing, using the interventions, communities, populations and evaluation methods they choose. As a result, after 15 years of dedicated, passionate and sometimes smart community-level food work, we still know too little to answer to such basic questions as:

1. How can better nutrition education contribute to more effective impact from policies such as menu calorie labeling, free school lunches or Health Bucks?

2. What characteristics of supermarkets other than proximity or size influence consumers to purchase and consume healthier food?

3. What is the relative influence of improving outreach and education programs for public food benefits such as SNAP and WIC compared to strategies to lower enrollment barriers?

Six Steps to Creating Evidence for More Useful Evaluation of Community Food Interventions

If five or ten years from now we are still unable to provide evidence about what works and what doesn’t work to reduce diet-related diseases and food insecurity in New York City’s poor neighborhoods, the burdens these two food problems are imposing on current generations will persist for at least another generation or more. By ourselves, the food policy and food justice communities will not be able to address the deeper determinants of the food related problems affecting New York City. But together we can do more to ensure that we will have the evidence we need to make more informed decisions in the years to come.

In closing, I suggest a few steps that may help to move to more systematic and useful evaluation of community food initiatives in New York City. My goal is to spark a deeper discussion of how best we can work together to learn from what we are doing now so we can do it better in the future.

1. Document and analyze practice-based evidence. Too often researchers, policy makers and funders privilege “evidence-based practice” that emerges only from controlled trials of well-defined interventions. Evidence-based interventions play an important role in shaping practice but these studies are expensive and often define the research questions so narrowly that generalizing findings to the real world is difficult. Lawrence Green, a public health researcher who has spent decades evaluating health promotion interventions, has called as well for “practice-based evidence”, lessons derived from the frontline experiences of hundreds of practitioners.[17],[18] By better documenting and assessing real world practice, practitioners can create a systematized body of practice-based evidence that, with the findings from evidence-based interventions, can provide a wider and more flexible guide to improving community food environments.

2. Bring the voices of community residents and frontline practitioners into evaluation. Academics sometime mystify evaluation—as if only those with a PhD in statistics can conduct such studies. Statisticians are an essential part of an evaluation team but so are community residents and frontline staff of community food programs. Any evaluation that does not answer their questions or incorporate their experiences and wisdom is missing essential pieces of the puzzle of why and how a program works or doesn’t work. New approaches to participatory research and community engagement in evaluation provide guidelines for organizations and evaluators who want to incorporate these valuable perspectives into evaluation.[19],[20]

NYCHA residents enjoying smoothies from Cafe Express, a community-driven food project run by SCAN-NY as part of the Building Healthy NYCHA Communities Through Food Initiative. Photo courtesy of SCAN-NY.

3. Establish standard measures of process, impact and outcome. Currently, most public and nonprofit food organizations and their evaluators develop their own surveys, environmental assessments, and focus group questions for any evaluation study they conduct. Certainly there is some need to tailor questions to a particular context or population. But the heterogeneity of the tools used makes it difficult to learn lessons across sites, populations and interventions types. In a counter example, the Healthy Food Retail Action Network, an association of staff of community-based, government, business and academic organizations working to improve retail food environments in New York City, has established an evaluation committee. This group, which operates mostly without outside funding, reviews and approves standard questions that are used across organizations to assess the impact of retail interventions. Such an approach does not require an evaluation czar who imposes arbitrary rules on participants. Rather, a “coalition of the willing” steps forward to develop shared intellectual property that can then guide policy and practice.

4. Define realistic expectations for evaluation studies. Participants in evaluation bring grand hopes to the evaluation process. Program managers want the documentation of impact that will support their next round of funding. Policy makers and funders want to show their backing improved the community. Evaluators want a peer-reviewed publication. Sometimes these hopes collide with the modest scope and resources for evaluation. While every program has the potential to evaluate some part of their work and any budget can support some evaluation activities, aligning the scope of the evaluation with the time and resources available can be a challenge. In general, evaluation of the process of implementation takes less time and costs less than evaluation of short term impact or long term outcomes. By bringing together key players such as program directors, frontline staff, funders, community participants and evaluators early in the program planning process, these constituencies can agree on a scope of evaluation, evaluation questions and methods that are consistent with the resources available. Nothing is more wasteful –and frustrating for all parties– than to begin a robust evaluation and then run out of time or money before any conclusions can be drawn.

5. Develop methods to evaluate cumulative impact of multiple food interventions. No single intervention is likely by itself to reverse the rising rates of obesity and overweight or to make hunger history in New York City. From tobacco control interventions in New York City and elsewhere, we learned that it was the cumulative impact of multiple interventions (e.g., increased tobacco taxes, smoking bans, warning labels, restrictions on sales to minors and others) that helped to bring the city’s smoking rates to historic new lows.[21] Changing diets will probably require the same multiplicity of interventions. For that reason, finding ways to look at the synergistic and cumulative impact of multiple interventions will provide important evidence as to whether or not we are moving in the same direction. In recent years, several investigators have started to use cumulative impact methods to look at food and other interventions, a practice that should be expanded.[22,23,24]

6. Evaluate equity impact of all food interventions. In New York City, racial/ethnic, socioeconomic and gender differences in food insecurity and diet-related diseases are key driving forces in the patterns of health inequalities. Interventions that decrease the prevalence of these conditions without simultaneously and forcefully reducing their inequitable distribution in the population risk perpetuating or even exacerbating these inequalities. For this reason, evaluation of community food interventions should assess their impact on both more and less advantaged populations to make sure that the gaps are shrinking. Since better off people often find it easier to use and benefit from innovations, any evaluation that does not include such a comparison may show that, for example, fruit and vegetable consumption is increasing among the poor. However, if these increases are larger in the better off, the gap will persist or widen. Several scholars have described various approaches to evaluating the equity impact of community health interventions.[25.26.27] Others discuss ways to measure changes in community capacity as a result of intervention.[28,29,30]

A related equity problem is that some organizations, such as larger nonprofit, government or academic institutions, often have an easier time getting the resources needed for more rigorous evaluations than smaller community organizations. As a result, the lessons from the interventions led by groups most intimately connected to vulnerable populations are less likely to be documented and to reach policymakers and foundations. By making reductions of this inequitable access a priority, funders of evaluation studies can level this playing field.

Few organizations have the resources or mandates to take all these steps on their own but every group can do something to better document the lessons from its experience. And together, practitioners, activists, policy makers, funders and evaluators can create a learning community that can ensure that a few years from now we’ll know more about what works to create healthier, more equitable community food environments than we do today.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Nevin Cohen, Ashley Rafalow, Michele Silver and Craig Willingham for their helpful suggestions for this commentary and to the staff at the community food programs sponsored by Bedford Stuyvesant Redevelopment Corporation, City Harvest, LISC-New York City, the NYCHA Urban Agriculture Initiative and United Neighborhood Houses for all they have taught me and my colleagues about the implementation and evaluation of community food programs. We would also like to thank Rick Luftglass, Laurie M. Tisch and the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund for their generous support for the creation and evaluation of several of New York City’s community food programs.

References

[1] Some useful guides to logic models and food interventions: National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Community Nutrition Education (CNE) Logic Model. USDA; 2015; National Research Center. Community Food Project Evaluation Handbook. USDA Community Food Projects Program, Third Edition, 2006, pp. 11-28; Corporation for National and Community Service. How to Develop a Program Logic Model. 2016.

[2] Airoldi, M., Morton, A.: Portfolio decision analysis for population health. In: Salo, A., Keisler, J., Morton, A. (eds.) Portfolio decision analysis: improved methods for resource allocation. Springer, New York (2011)

[3] Rodriguez-García R. A Portfolio Approach to Evaluation: Evaluations of Community-Based HIV/AIDS Responses. Poverty, Inequality, and Evaluation. 2015:139.

[4] Almog-Bar M, Schmid H. Advocacy activities of nonprofit human service organizations: A critical review. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2014;43(1):11-35.

[5] Garrow EE, Hasenfeld Y. Institutional logics, moral frames, and advocacy: Explaining the purpose of advocacy among nonprofit human-service organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2014; 43(1):80-98.

[6] Teles S, Schmitt M. The elusive craft of evaluating advocacy. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 201; 9(3):40-3.

[7] Coffman J. What‘s Different about Evaluating Advocacy and Policy Change?’. The Evaluation Exchange. 2007; 13(1):2-4.

[8] Devlin-Foltz D, Fagen MC, Reed E, Medina R, Neiger BL. Advocacy evaluation: challenges and emerging trends. Health Promot Pract. 2012; 13(5):581-6.

[9] Barriuso L, Miqueleiz E, Albaladejo R, Villanueva R, Santos JM, Regidor E. Socioeconomic position and childhood-adolescent weight status in rich countries: a systematic review, 1990-2013. BMC Pediatr. 2015; 15:129.

[10] Otero G, Pechlaner G, Liberman G, Gürcan E. The neoliberal diet and inequality in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2015; 142:47-55.

[11] Siddiqi A, Brown R, Nguyen QC, Loopstra R, Kawachi I. Cross-national comparison of socioeconomic inequalities in obesity in the United States and Canada. Int J Equity Health. 2015; 14:116.

[12] Sommeiller E, Price M, Wazeter E.Income inequality in the U.S. by state, metropolitan area, and county. Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute, 2016.

[13] Pudrovska T, Logan ES, Richman A. Early-life social origins of later-life body weight: the role of socioeconomic status and health behaviors over the life course. Soc Sci Res. 2014; 46:59-71.

[14] Cozier YC, Yu J, Coogan PF, Bethea TN, Rosenberg L, Palmer JR. Racism, segregation, and risk of obesity in the Black Women’s Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2014; 179(7):875-83.

[15] Delavari M, Sønderlund AL, Swinburn B, Mellor D, Renzaho A. Acculturation and obesity among migrant populations in high income countries–a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13:458.

[16] Boyland EJ, Nolan S, Kelly B, Tudur-Smith C, Jones A, Halford JC, Robinson E. Advertising as a cue to consume: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of acute exposure to unhealthy food and nonalcoholic beverage advertising on intake in children and adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016; 103(2):519-33.

[17] Green LW. Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where’s the practice-based evidence? Fam Pract. 2008; 25 Suppl 1:i20-4.

[18 ] Green LW. Public health asks of systems science: to advance our evidence-based practice, can you help us get more practice-based evidence? Am J Public Health.2006;96(3):406-9

[19] Nitsch M, Waldherr K, Denk E, Griebler U, Marent B, Forster R. Participation by different stakeholders in participatory evaluation of health promotion: a literature review. Eval Program Plann. 2013; 40:42-54.

[20] O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S, Kavanagh J, Jamal F, Thomas J. The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015; 15:129.

[21] Kilgore EA, Mandel-Ricci J, Johns M, Coady MH, Perl SB, Goodman A, Kansagra SM. Making it harder to smoke and easier to quit: the effect of 10 years of tobacco control in New York City. American journal of public health. 2014; 104(6):e5-8.

[22] Kania J, Kramer M. Embracing emergence: How collective impact addresses complexity. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Blog entry, 2013; 21.

[23] Christens BD, Inzeo PT. Widening the view: situating collective impact among frameworks for community-led change. Community Development. 2015; 46(4):420-35.

[24] Flood J, Minkler M, Hennessey Lavery S, Estrada J, Falbe J. The Collective Impact Model and its potential for health promotion: overview and case study of a healthy retail initiative in San Francisco. Health Education & Behavior. 2015; 42(5):654-68.

[25] Backholer K, Beauchamp A, Ball K, Turrell G, Martin J, Woods J, Peeters A. A framework for evaluating the impact of obesity prevention strategies on socioeconomic inequalities in weight. American journal of public health. 2014; 104(10):e43-50.

[26] McGill R, Anwar E, Orton L, Bromley H, Lloyd-Williams F, O’Flaherty M, Taylor-Robinson D, Guzman-Castillo M, Gillespie D, Moreira P, Allen K. Are interventions to promote healthy eating equally effective for all? Systematic review of socioeconomic inequalities in impact. BMC public health. 2015; 15(1):457.

[27] Benach J, Malmusi D, Yasui Y, Martínez JM. A new typology of policies to tackle health inequalities and scenarios of impact based on Rose’s population approach. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2013; 67(3):286-91.

[28] Downey LH, Castellanos DC, Yadrick K, Threadgill P, Kennedy B, Strickland E, Prewitt TE, Bogle M. Capacity building for health through community-based participatory nutrition intervention research in rural communities. Fam Community Health. 2010; 33 (3):175-85.

[29] Sharpe PA, Flint S, Burroughs-Girardi EL, Pekuri L, Wilcox S, Forthofer M. Building capacity in disadvantaged communities: development of the community advocacy and leadership program. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2015; 9(1):113-27.

[30] Liberato SC, Brimblecombe J, Ritchie J, Ferguson M, Coveney J. Measuring capacity building in communities: a review of the literature. BMC Public Health 2011; 9;11:850.