1. Why is democracy a problem in our society today? How are democracy problems connected to food problems?

In the last few years, democracy has encountered several challenges here in New York City and nationally:

- After a few elected officials and local activists challenged the agreement that Amazon had negotiated with New York City and State, mostly in secret, a deal that included $3 billion in public subsidies and tax breaks for one of the world’s biggest companies, Amazon rescinded its offer. Some of the sponsoring elected officials accused critics of opposing jobs and of “governmental malpractice”, rather than criticizing Amazon for its efforts to bypass democratic processes.1

- In the 2018 New York State elections, just 100 people donated more to candidates than all the 137,000 estimated small donors combined,2 illustrating the continuing disproportionate influence of the very wealthy in our electoral system.

- Nationally, several conservative groups have made voter disenfranchisement a priority, seeking to disenroll voters; charging widespread voter fraud despite the lack of evidence to substantiate such claims, and launching campaigns designed to discourage legal immigrants, Blacks and Latinos, and other groups from exercising their right to vote.3

Our food system also illustrates problems related to democracy. In 2015, A & P, a national super market chain, went bankrupt and closed the Pathmark on 125th Street and Lexington Avenue that had opened almost 20 years earlier as a result of community mobilization and pressure to make healthy food more available and affordable in Central and East Harlem. Closing the store forced more than 200 workers to look for new jobs and deprived many older and low-income people living in the many public housing projects nearby of a convenient site to buy relatively healthy, relatively affordable food. Now, almost three years later, the site is still vacant as Extell, the new owner, a major housing development company, waits for more propitious conditions to build new luxury housing on the site. Meanwhile, a year or so later, Whole Foods, now owned by Amazon, opened a new store a few blocks away on 125th Street. This store is now bustling but many long-time Harlem residents are unable to afford the prices they charge.

What does this have to do with democracy? Not a single Harlem resident voted whether to close Pathmark or open Whole Foods. These decisions, which profoundly influence access to healthy foods, were made by private companies with no consideration of the public impact. Current conceptions of democracy preclude voters, residents or tax payers from having a meaningful voice in shaping local food environments.

Another food policy decision illustrates the unlevel playing field in which food decisions are made. When the Bloomberg administration proposed in 2012 to limit the portion size of sugary beverages to reduce obesity and diet related disease, the sugary beverage industry mobilized to defeat the proposal. After the city’s Board of Health approved the portion size limitation, the soda industry trade groups went to court challenging the Board’s power to make such a rule. In 2014, the New York Court of Appeals, the state’s highest court, ruled that the New York City Board of Health, in adopting the Sugary Drinks Portion Cap Rule, exceeded the scope of its regulatory authority and overturned it.4

Between 2009 and 2015, the beverage industry spent more than fifteen million dollars in New York State campaigning against the Portion Cap Rule and other nutrition-related initiatives, including an earlier proposed statewide soda tax.5

In 2009, as Congress discussed a federal tax on SSBs to help finance the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, the soft drink industry spent $40.7 million in a successful lobbying that contributed to the proposal being dropped. The 2009 spending was a dramatic increase from $2.8 million spent in 2006.6

The soda industry’s deep pockets for lobbying and litigation enabled it to frame the political and legal discussions on soda taxes and other public health measures to reduce diet-related diseases. Through its ability to dominate the policy debates, the soda industry deprived citizens of having a balanced public debate on a level playing field on an important public health strategy.

2. What is food democracy?

Food democracy is central to the advancement of equitable, healthy, and sustainable urban food systems. In a food democracy, all members of the agro-food system have equal and effective opportunities to design, operate, and participate in its stewardship.7

Citizens are fully aware of their rights and responsibilities, partake in decision-making at different scales – city, state, federal, and international, and no longer see themselves, or behave, as passive consumers. An active food polity arises and uses food democracy as a tool to empower disenfranchised individuals and communities and to influence food system outcomes. Society writ large leverages food democracy to make decisions on contested food system issues or cope with problems with no clear single solution. How can New York and other jurisdictions move from our current situation to this more visionary state?

The gist of food democracy is to expose nondemocratic forms of influence and control of the current food system and bring about greater food justice. In other words, as urbanites transition from mere observers, or marketing targets, to woke “food citizens,” they can act to shrink disparities in access to affordable healthy, nutritious, and culturally appropriate foods. Some food democracy theorists refer to this process as the “moralization” (or “civilization”) of food economies,8 which is about recasting the relationships between civil society, state, and market players in the agro-food system. In a global perspective, food democracy initiatives are commonly animated by the desire to ensure that “privileged core regions do not live off the carrying capacity of the periphery.”9

Importantly, food democracy cannot exist in the absence of food sovereignty. Food sovereignty sets the goal of “placing control of food systems into the hands of those most often disregarded and oppressed by corporate-driven food systems.”10

The literature has commonly focused on the empowerment of farmers and “agrarian citizenship” but the concept has wider applications to all segments of the food chain – from seed to fork. Transfer of power is in part catalyzed through more hybrid, decentralized roles for both producers and consumers, captured in part by terms such as “co-producers” or “prosumers,” as well as decentralized wealth and opportunities for durable jobs and business ownership by the communities most affected by food injustices.

Most recent developments in food democracy scholarship have called for a bolder framework for action – “deep food democracy”11 – that would amplify the impact of multiple streams of food democracy work. Deepening food democracy entails transitioning from elitist “voting with your fork” slogans to universal “voting with your vote” values and asks governments and companies to re-envision citizens’ voice as not just valuable but essential in decision-making processes. It is about transforming both politics and institutions. Over the past decade, each has grown increasingly polarized and it has been difficult to make room for civic participation that goes beyond including the usual, loudest voices in the room. Deep food democracy emerges when there is an alignment between transparent institutions, open food system knowledge, engaged citizenship, and real opportunities for transformative action for all.

3. What is the state of food democracy and what existing processes could strengthen food democracy?

The past several decades of food activism in the US and elsewhere, have started — if haphazardly and from the margins — to questions the dominant food and agriculture economy. Occasionally, these changes have had important reverberations in public policy. Yet more work remains to be done to fulfill the ideals of deep food democracy. The decentralization and redistribution of power both in decision-making and food system building processes call for initiatives that sustain and amplify existing mechanisms for democratic participation and stabilize fledgling food system innovations.

Decision-Making

Evidence shows a surge in initiatives to decentralize food policy decision-making. New political spaces like city and regional food policy councils, municipal food boards, interdepartmental food policy task forces, and food policy units within the mayor’s office were virtually nonexistent fifty years ago. Today, there are more than 260 active food policy councils in the US alone, nearly 60 in Canada, 12 and many more in the making around the world. This is a remarkable achievement compared to the handful of these organizational innovations which existed in the 1990s.13

Food policy councils and similar institutions may greatly vary in institutional home — inside or outside government — or constituents — farmers, urban gardeners, emergency food providers, retailers, chefs, waste management companies, policymakers, academics, entrepreneurs — but all share the enterprise of making the urban food system visible and catalyze democratic deliberation on its most pressing challenges.

In addition to the rapid diffusion of local food policy councils throughout North America and Western Europe, regional and national networks of these spaces have also started taking shape. [The Food Policy Task Force][0] in the US Conference of Mayors and the [Sustainable Food Cities][1] network in the UK are two clear examples of a second, scaled-up layer of decentralization of food governance. The codification of knowledge is yet another example of the scaling up of these organizational innovations. Drawing lessons on several decades of trial and error, seasoned food policy entrepreneurs have contributed to the development of toolkits and manuals14 on how to effectively establish and direct food policy councils from the ground up. A dedicated monitoring unit with the task of tracking and reporting on the state of food policy networks in the US and Canada has been established15 and develops yearly reports on the topic.

Yet, evidence also points to the fragility of emergent spaces for food democracy. While the number of food policy councils has steadily risen over the past twenty years, the majority are still understaffed and underfunded.16,17

What is more, less than 12% of these spaces are seated within government agencies or departments and only 15% receive funding from city, county, state or federal government, thus extensively relying on in-kind donations and grants. Ultimately, while there are promising developments at the national and international level — such as the recent thrust for a “Common Food Policy” in Europe18— we are yet to witness the establishment of a City Department of Food and shifts in administration often jeopardize the permanence of these budding food democracy institutions. Other democratic mechanisms like participatory budgeting and the development of community-based plans exist at the city level, but currently are largely underutilized for the advancement of food justice goals.

Despite their limitations, novel food governance spaces have often filled an institutional void and served as de facto food system planning agencies.19

These policy networks have been instrumental in ushering a new stage of the good food movement and its institutionalization in local policy discourses and practices. To the food policy entrepreneurs animating them, we owe the inclusion of community food system goals in comprehensive sustainability plans 20 or adoption of comprehensive policies, such as the Good Food Purchasing Program, by local administrations. Further, the 2018 Farm Bill set a precedent by mandating the establishment of a new Office of Urban Agriculture and Innovative Forms of Production within the US Department of Agriculture and authorized Congress to appropriate up to $25 million per year to support local urban agriculture and organic food waste reduction efforts.21

Food System Building

Practicing food democracy means not just participating in decision-making processes, crucial as that is, but also crafting more inclusive policies and systems that enable food citizenship and more equitable food economies — from production to distribution, consumption, and post-consumption and nutrient management. Alongside the upsurge of new political spaces for food democracy, an abundance of projects and initiatives seeking to disrupt established food system structures of power has emerged. Grassroots innovations and place-based food networks have added a new set of relationships between government, market, and civil society.22

This, at times, has resulted in greater equity and resiliency of the food system through higher diversity and redundancy of both goods and services in the system as a whole.

In the United States, a key goal of food democracy has been to illuminate and reduce deep and persistent racial/ethnic inequalities in our food system. Books like The Color of Food: Stories of Race, Resilience, and Farming, concepts like [food apartheid][2], and the emergence of local, regional and national networks dedicated to tackling racism in the food system testify to this stream of work.

Critical observers nevertheless warrant that it is not uncommon that “alternative” food initiatives perpetuate rather than dismantle entrenched inequalities, since they still operate within dominant neoliberal market and social structures. Put simply, nothing prevents a farmers’ market or an urban farm from being more unsustainable or unequal than a conventional supermarket or a large-scale industrial farm. In fact, decentralized, local food systems per se are not a guarantee for more equitable distribution of power and opportunities and thus are not a silver bullet for deepening food democracy. In fact, as food governance analysts observe, “food-democracy cannot be achieved without the democratization of all institutions.”23

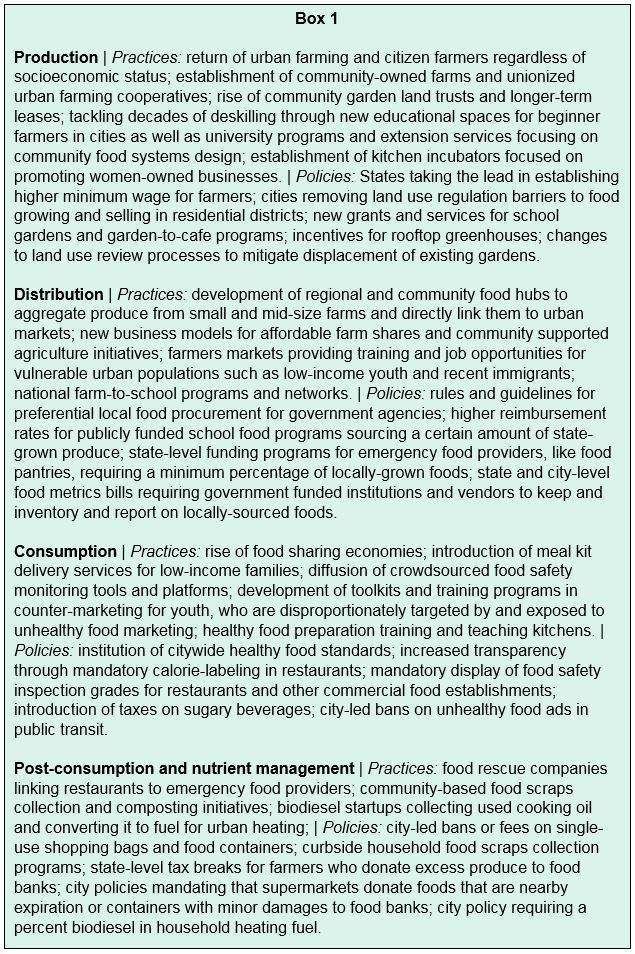

With this caution in mind, it is fair to say that, opportunities for more hybrid and nonexclusive food systems building initiatives have been significantly expanded over the past couple of decades. Box 1 shows some examples of practices and policies pointing in that direction across different spheres of the food system.

4. What are the limitations of current approaches to strengthening democracy and food democracy and how can we overcome them?

To expand and strengthen democracy, including food democracy, will require deep analysis of the immediate and fundamental causes of current threats to democracy. In parallel, food justice and democracy activists will need to forge in practice both short term and incremental strategies and longer term, more transformational ones.

In the last decade, democracy activists have developed a variety of approaches for protecting and enhancing democracy. These include voter registration drives and litigation to challenge disenfranchisement; state and local laws to limit and require disclosure of lobbying and campaign contributions; and creation of public rather than only private support for electoral campaigns. New York City’s Ten Point Democracy Initiative is one illustration of such an agenda.

On the food side, food policy councils, participatory budgeting and ballot initiatives on issues such as soda taxes are examples of recent efforts to give voters a bigger voice in shaping food environments. These approaches have had varying levels of success in mobilizing communities and winning policy change.24

Transformative change, however, will require more structural corrections. In the last fifty years, corporations and the ultra-wealthy have won new power to shape politics, the economy—and food environments.25 Elites have used this new power to enact policies such as shifting more tax burden from the wealthy to the middle and working classes, cutting back New Deal and subsequent safety net programs that protected vulnerable populations from economic downturns, expanding the constitutional rights of corporations to have a voice in elections and policy, and loosening the public health, environmental and consumer protections enacted in the 1960s and 1970s. Restoring and refreshing democracy in the United States necessitates a long-term strategy to restore a fairer balance of power.

In food policy, the rising power of agribusiness and large transnational food corporations has led to a similar power imbalance. To create more democratic food governance will necessitate reducing corporate power and increasing public and local control of food systems. Possible goals for such a redistribution of power would be stronger institutional food programs, stricter regulation of deceptive and misleading food marketing, a more robust and better funded public sector in food and a return to the more vigorous enforcement of antitrust policies of the early twentieth century.

On the one hand, food democracy sometimes seems like an idealistic, perhaps naïve goal. On the other hand, what could be more basic than having a right to shape the food environments that play such a vital role in promoting health, affirming identity and bringing joy?

References

1 J. David Goodman and Karen Weise Why the Amazon Deal Collapsed: A Tech Giant Stumbles in N.Y.’s Raucous Political Arena. The New York Times, February 16, 2019, p. A1.

2 Chisun Lee, Nirali Vyas. Analysis: New York’s Big Donor Problem & Why Small Donor Public Financing Is an Effective Solution for Constituents and Candidates Brennan Center for Justice. January 28, 2019, https://www.brennancenter.org/analysis/nypf#_ftn2

3 By Danielle Root and Adam Barclay Voter Suppression During the 2018 Midterm Elections . A Comprehensive Survey of Voter Suppression and Other Election Day Problems. Center for American Progress, November 20, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/democracy/reports/2018/11/20/461296/voter-suppression-2018-midterm-elections/

4 Michael M. Grynbaum .New York’s Ban on Big Sodas Is Rejected by Final Court, New York Times , June 27, 2014, p.A24.

5 Soda Industry Spending Against Public Health Tops $100 Million: Spending Since 2009 Targets Taxes, Warning Label Measures, CTR. FOR SCI. PUB. INT. (Aug. 25, 2015), https://cspinet.org/new/201508251.htm

6 Wilson D, Roberts J. Special report: how Washington went soft on childhood obesity. Reuters. 2012 April 27.

7 Hassanein, N. (2003). Practicing food democracy: a pragmatic politics of transformation. Journal of Rural Studies, 19(1), 77-86.

8 Renting, H., Schermer, M., & Rossi, A. (2012). Building food democracy: Exploring civic food networks and newly emerging forms of food citizenship. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 19(3), 289-307.

9 Johnston, J., Biro, A., & MacKendrick, N. (2009). Lost in the supermarket: the corporate‐organic foodscape and the struggle for food democracy. Antipode, 41(3), 509-532.

10 Jill Carlson & M. Jahi Chappell. (2015). Deepening Food Democracy: The tools to create a sustainable, food secure and food sovereign future are already here—deep democratic approaches can show us how. Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/2015_01_06_Agrodemocracy_JC_JC_f_0.pdf.

11 Jill Carlson & M. Jahi Chappell. (2015). Deepening Food Democracy: The tools to create a sustainable, food secure and food sovereign future are already here—deep democratic approaches can show us how. Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/2015_01_06_Agrodemocracy_JC_JC_f_0.pdf.

12 Lily Sussman & Karen Bassarab (2017). Food Policy Councils Report 2016. Retrieved from: https://assets.jhsph.edu/clf/mod_clfResource/doc/FPC%20Report%202016_Final.pdf

13 Pothukuchi, K., & Kaufman, J. L. (1999). Placing the food system on the urban agenda: The role of municipal institutions in food systems planning. Agriculture and human values, 16(2), 213-224.

14 Mark Winne Associates (2012) Doing Food Policy Councils Right. A Guide to Development and Action, https://www.markwinne.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/FPC-manual.pdf

15 http://www.foodpolicynetworks.org/about/

16 Food First (2009) Food Policy Councils: Lessons Learned https://foodfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/DR21-Food-Policy-Councils-Lessons-Learned-.pdf

17 Lily Sussman & Karen Bassarab (2017). Food Policy Councils Report 2016. Retrieved from: https://assets.jhsph.edu/clf/mod_clfResource/doc/FPC%20Report%202016_Final.pdf

18 IPES (2018). Towards a Common Food Policy for the EU. http://www.ipes-food.org/pages/CommonFoodPolicy

19 Winne, M. (2004) Food system planning: Setting the community’s table. Progressive Planning. 158. 13-15.

20 Hogston, K. (2012). Planning for Food Access and Community-Based Food Systems, APA. https://www.planning.org/publications/document/9148238/

21 http://sustainableagriculture.net/blog/2018-farm-bill-drilldown-local-rural/

22 Renting, H., & Wiskerke, J. S. C. (2010). New emerging roles for public institutions and civil society in the promotion of sustainable local agro-food systems.

23 Food Secure Canada. (2013) Food Democracy and Governance: Towards a People’s Food Policy Process. Discussion Paper 10. https://foodsecurecanada.org/sites/foodsecurecanada.org/files/DP10_Food_Democracy_and_Governance_0.pdf Read more here.

24 See for example: Alkon A, Guthman J, eds. The new food activism: Opposition, cooperation, and collective action. Univ of California Press; 2017; Carlson J, Chappell MJ. Deepening food democracy. Institute for Agriculture and Trade policy, 2015; Rossi A. Beyond food provisioning: the transformative potential of grassroots innovation around food. Agriculture. 2017 Jan 19;7(1):6. Chiffoleau Y, Millet-Amrani S, Canard A. From short food supply chains to sustainable agriculture in urban food systems: Food democracy as a vector of transition. Agriculture, 2016 6(4), 57.

25 See for example: Clapp J, Fuchs DA. Corporate Power in Global Agrifood Governance. United Kingdom: MIT Press, 2009; Mikler, J. The Political Power of Global Corporations. United Kingdom: Wiley, 2018; Soederberg, S. Corporate Power and Ownership in Contemporary Capitalism: The Politics of Resistance and Domination. (n.p.): Taylor & Francis, 2009.