Since the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York City in March 2020, many city residents have been pushed into food insecurity. In response, the city, state, and federal governments and non-profit anti-hunger groups have launched new food assistance programs and expanded existing ones. As the pandemic worsens, a key question is to what extent have these efforts met the growing need for food in New York City. Results from the CUNY School of Public Health COVID-19 Survey, a series of polls of 1,000 New York City residents conducted at periodic intervals over the last eight months, suggest some answers. [1]

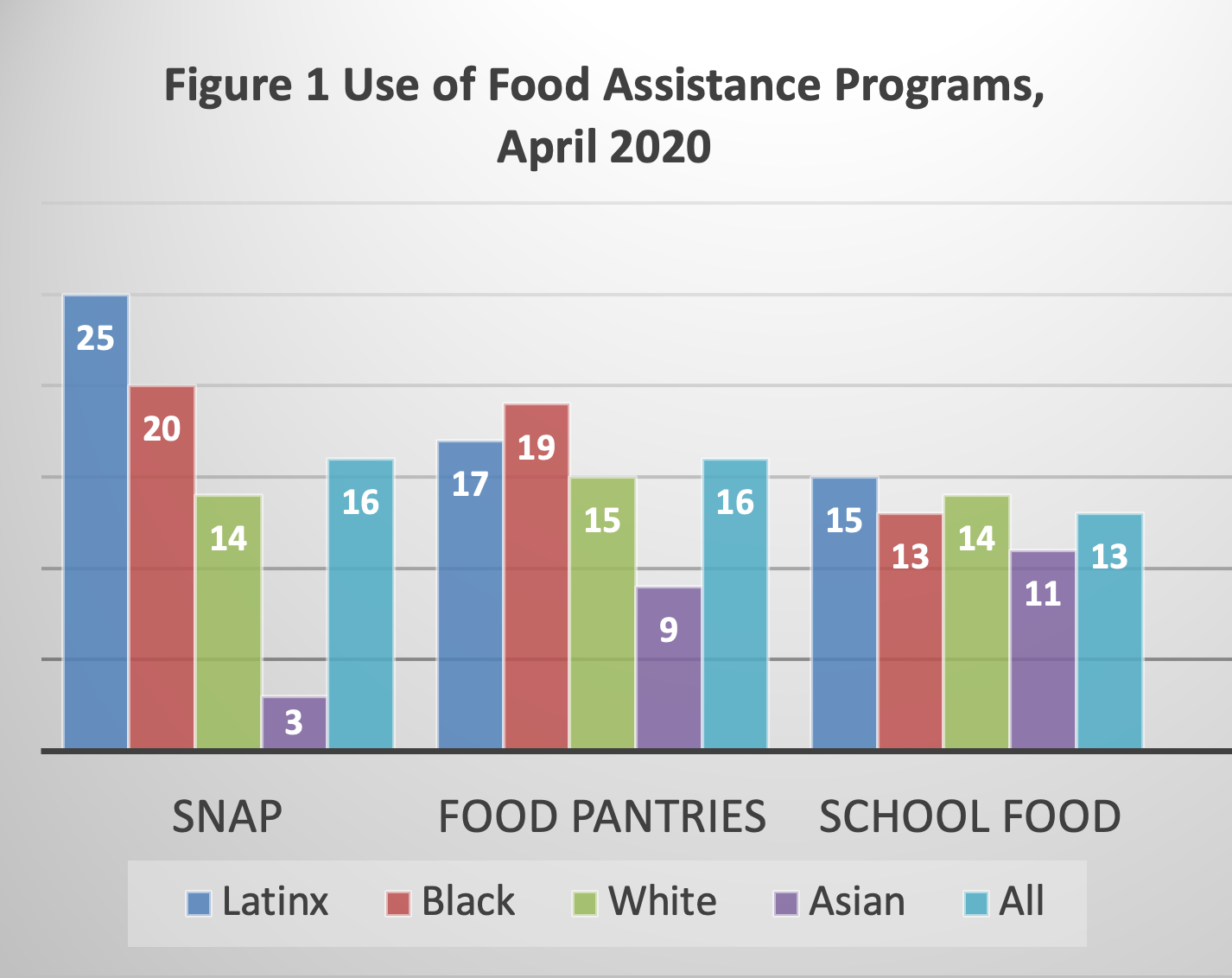

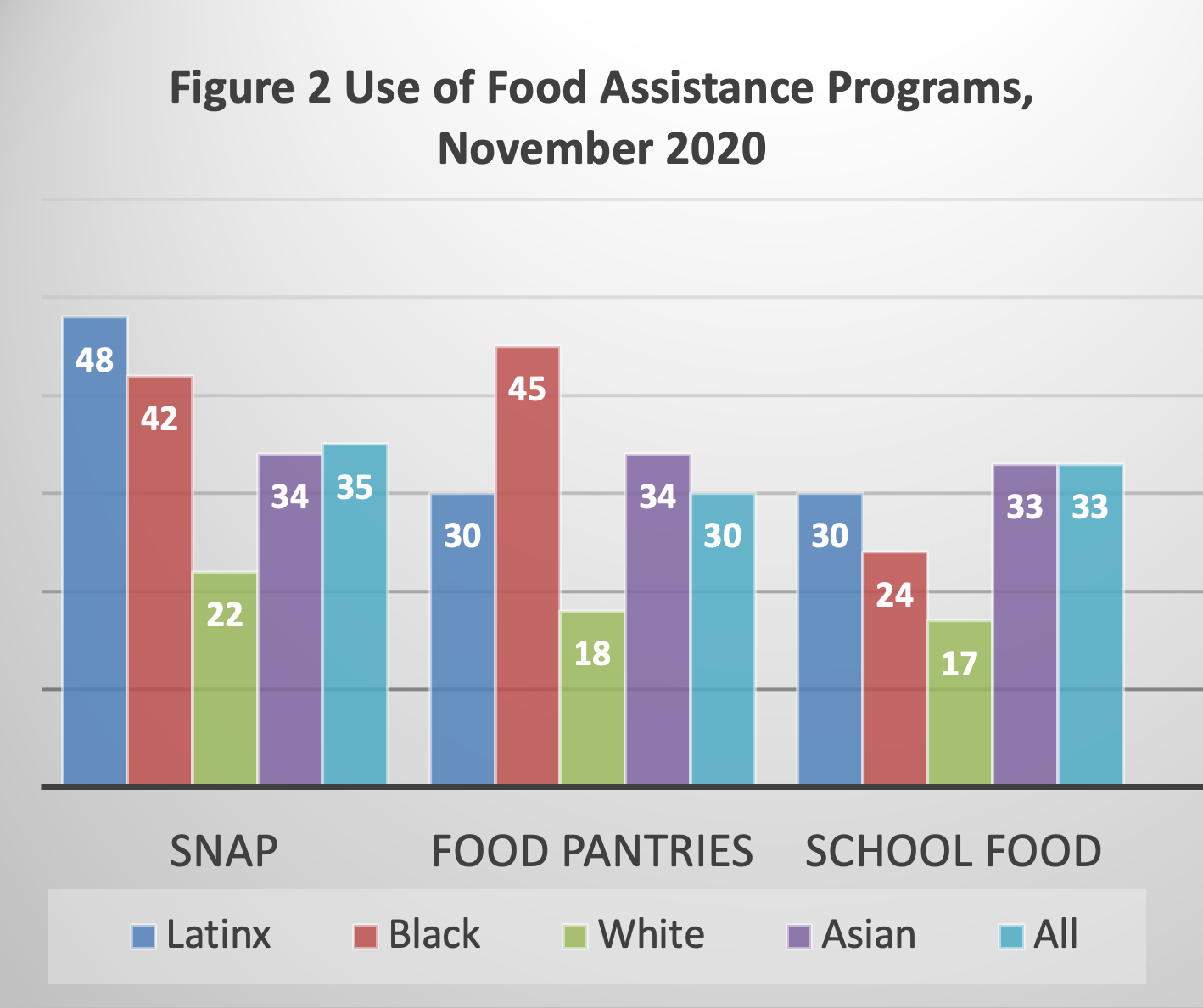

Poll results show that between April and November 2020, participation in three key public food programs increased significantly. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, over this eight-month period, the proportion of New Yorkers responding to the CUNY SPH poll who reported using SNAP (formerly known as Food Stamps) in the last month almost doubled, from 16% to 35%. During this period, the city and state used new federal authorization to expand SNAP through a variety of measures. [2]

During this same eight months, the proportion of survey respondents who received food from emergency food programs such as food pantries or soup kitchens increased from 16% to 30%, almost double the rate of participation. Similarly, the proportion of families who received food from any of the programs offered by the New York City school food program, including Grab and Go Meals, Pandemic EBT, and others increased from 13% of all respondents in April to 33% in November, a more than 2.5-fold increase. These increases constitute a remarkable accomplishment for the public and nonprofit organizations that address food insecurity and hunger in New York City

Both before and during the pandemic, other studies have shown that rates of food insecurity were higher among Black and Latinx populations compared to whites. How did participation in the three public food programs by these racial/ethnic groups change over the first eight months of the pandemic?

As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the proportion of survey respondents in each of the four major racial/ethnic groups in New York City who participated in public food programs increased between April and November. However, rates of change by race/ethnicity varied considerably. The proportion of Asian residents participating in SNAP increased more than tenfold, in part because prior to the pandemic SNAP-eligible Asians had lower enrollment rates than other groups. Compared to other racial/ethnic groups, the participation of white city residents in food pantries and school food programs increased the least, by “only” about 20% for food pantries and school food, compared to, for example, Latinx respondents whose participation rates in food pantries more than doubled and Asian respondents whose reported participation rate in school food tripled. In general, these results show that people of color increased use of public food programs more than whites, a finding consistent with higher rates of poverty, unemployment, and high housing costs in communities of color, both before and especially during the pandemic.

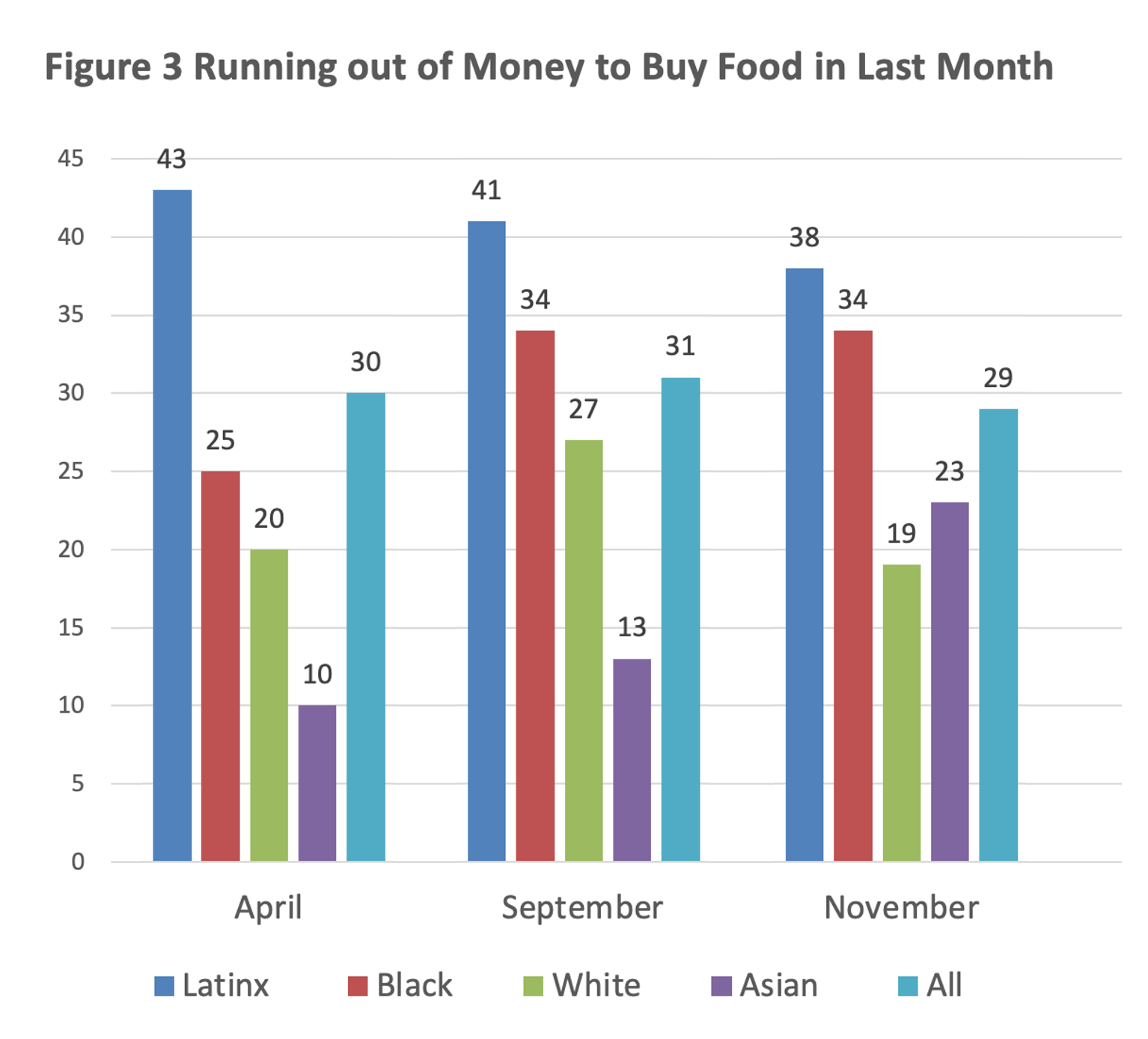

A key question is whether these higher rates of participation in food assistance programs helped to shrink the gap in measures of food insecurity between white and other racial/ethnic groups. Unfortunately, as Figure 3 shows, these gaps have persisted, even in the face of the remarkable expansion of city food programs.

Over the eight months from April to November 2020, the overall rate of New York City residents reporting running out of money to buy food in the last month stayed essentially flat, declining only 3%, from 30% to 29%. Latinx survey respondents reported a decline of almost 12% in running out of money, from 43% to 38%. Perhaps their higher participation rates in public food programs helped to reduce this indicator of food insecurity. Black and Asian respondents, however, each reported increases in running out of money for food, by 36% for Blacks (from 25% to 32%) and by 130% for Asians. The rates of white respondents running out of money for food declined modestly by 5%, from 20% in April to 19% in November.

Troublingly, over the eight months, despite the concerted and successful efforts to expand food assistance, the gap between the rates at which white New Yorkers and Black, Latino and Asian New Yorkers reported running out of money for food did not change. In both May and November people of color responding to the survey were almost twice as likely (1.8 times) to report running out of money for food as white New Yorkers. Another contributing factor to this indicator of persistent systemic racism is the higher level of pandemic-triggered and long-term unemployment among New Yorkers of color, a fact which further diminishes resources available for food.

As the pandemic again worsens, the challenge for New York City is to modify, expand and strengthen its food security initiatives to close the racial/ethnic gap in food security. The modest decline in reported food insecurity among Latinx New Yorkers over the eight months suggests that larger increases in participation in public food programs is associated with less food insecurity as measured by reporting running out of money for food. If achieving these higher participation rates for Black and Asian New Yorkers will similarly contribute to declines in food insecurity for these groups, new education and outreach efforts to enroll more people in public food benefits are essential.

In addition, increased support for unemployment benefits, extension of rental assistance, further increases in the minimum wage and, other measures that give New Yorkers more income to purchase food and other necessities of life can contribute to reducing food insecurity and hunger. In Washington, Congress and the incoming Biden Administration are considering pandemic emergency relief programs while in Albany, the Governor and New York State legislature debate tax increases on the wealthiest New Yorkers in order to avoid harsh austerity measures. Community organizations, food advocates, and New York City residents can raise their voices to urge that the city, state, and nation’s responses to the pandemic make our city a healthier and more equitable place to live rather than widen the racial/ethnic gaps that characterize New York today.

By Nicholas Freudenberg, Distinguished Professor of Public Health at the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health & Health Policy and Director of the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute

Endnotes

[1] The CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy (CUNY SPH) cross-sectional survey was conducted by Emerson College Polling in weekly, biweekly, and then monthly intervals beginning in mid-March 2020 to track the social, economic, health, and mental health impacts of COVID-19 from the initial onset of COVID-19 epidemic in New York City. This effort started March 13-15 and will continue into early 2021. Details of the survey methodology and its limitations can be found here. Results of the most recent survey in late November are here.

[2] Since March, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, states have used temporary SNAP flexibility to provide emergency benefit supplements, maintain benefits to households with children missing school meals, and ease program administration during the pandemic. These options have allowed states to deliver more food assistance to struggling families, help manage rising and ongoing administrative demands, and ensure that participants maintain much-needed benefits. This administrative flexibility has also facilitated growth in SNAP participation to meet increased need and ensure that families experiencing hardship can quickly get benefits to buy food.